From A. B. Hull’s homestead record located in the National Archives in Washington, D. C. the following: Homestead Proof-Testimony of Claimant: Albert B. Hull. On the 15th day of March 1886 Hull filled Homestead Entry Number 9656 on NW quarter of Section 23, Township 20, Range 58. In 1886, Hull states he is 28 years old and is a natural born citizen of the United States born in West Virginia.

The homestead house was built in May of 1886 and A. B. Hull established residence on May 20, 1886. He built a frame house 14 X 20 feet two stories high with a frame addition 10 X 20 feet, a sod stable 18 X 20 feet, a log shed 16 X 18 feet, a cave 18 X 20 (?) and a well 45 feet deep. A grass pasture of 120 acres was fenced with wire, and he broke 20 acres of farm ground. He cultivated this ground for 4 seasons and raised a crop each year.

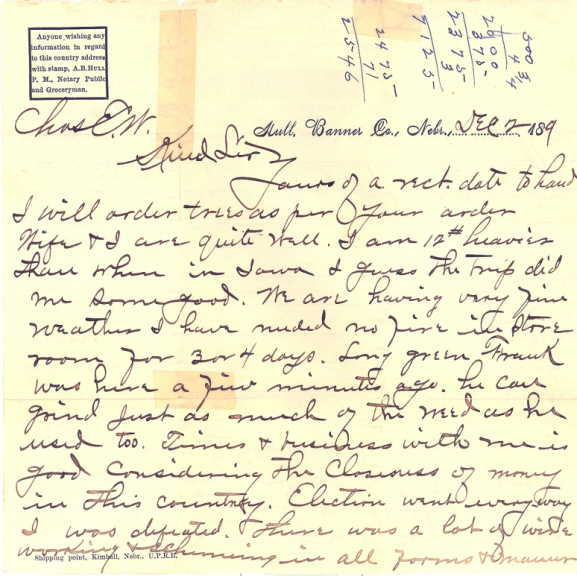

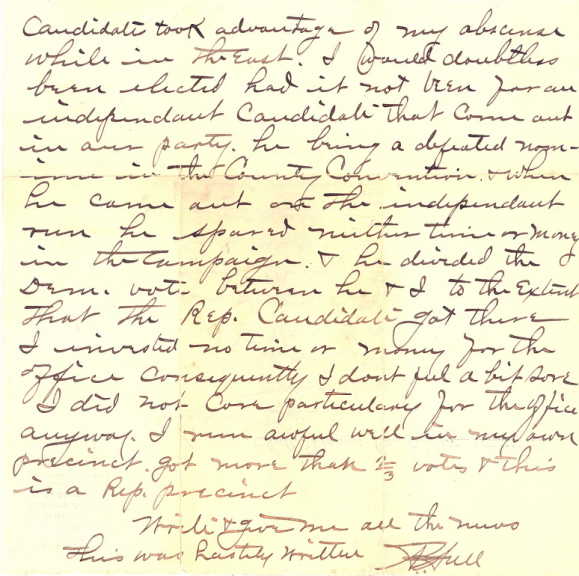

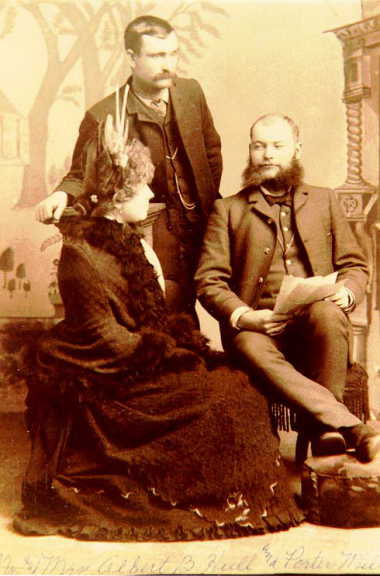

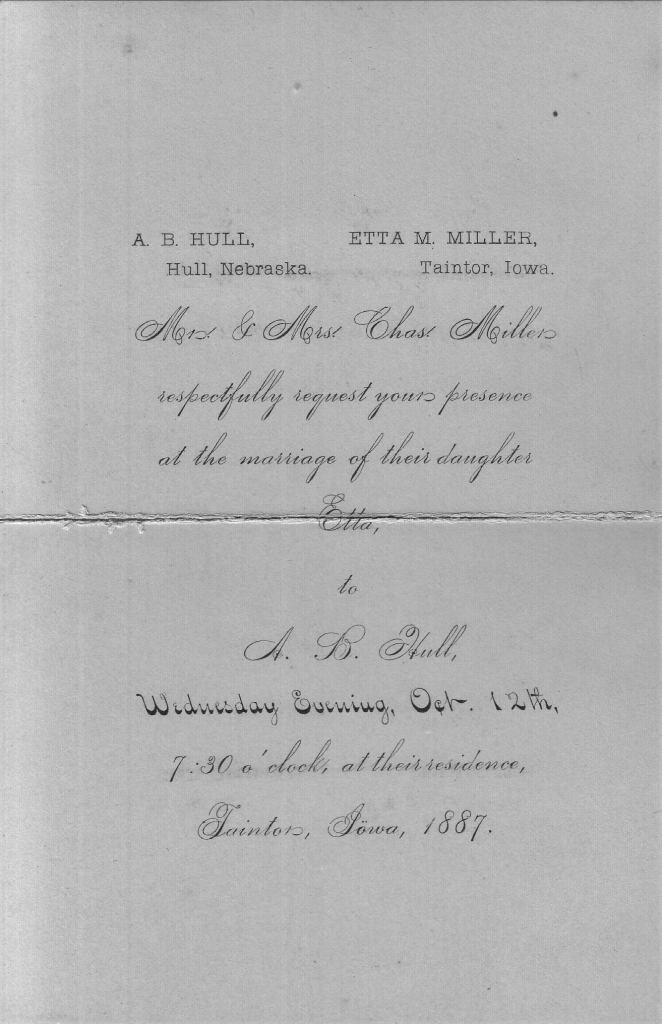

In September of 2020 contact was made with Jay Hull (great grandson) and he allowed permission to publish this story with the photos. A. B. Hull and Etta Miller’s wedding announcement is inserted in the story and one of his letters at the end. Notice the information on the letterhead.

Many thanks to Jay for use of the story, photos and the letter.

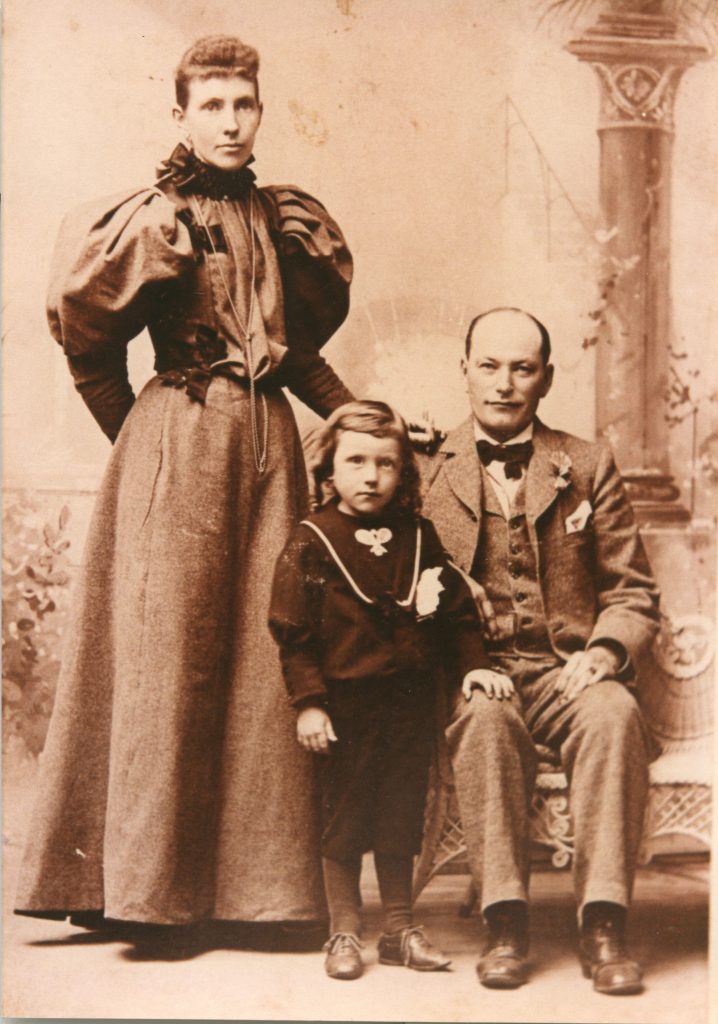

Albert Bristor Hull (1862-1937) and Etta Mae Miller (1865-1956)

By Jay G. Hull (grandson & nariator) and Junior G. Hull (great grandson & author)

Hull Family History, Chandler Farm Press, Wilder, Vermont (1985)

Albert Bristor Hull was born in Grafton, West Virginia November 6, 1862, two and one-half months after his father, Albert G. Hull, went to war. In fact, it is likely that he was named for his father’s company commander, Captain J.H. Bristor. Following the war, at the age of three he moved to Iowa with his father. He grew up in Iowa, working on his father’s farm.

On October 12, 1887, at the age of 24, Albert Hull married Etta Miller. The following year, the two homesteaded on the prairies of western Nebraska and settled the town that bears the family name: Hull (Banner County) Nebraska. Albert and Etta spent the first year establishing a country store and a rural post office in this northwestern section of Nebraska. There were no permanent roads and they were eighty miles from the nearest railroad. Mail was delivered by stage and was left with them to be picked up by ranchers and farmers when they came to town for supplies.

Albert and Etta Hull were living in Nebraska during the infamous winter of 1888. This winter stands as the most severe ever recorded on the great plains of the United States. Livestock perished by the thousands and there were numerous human casualties as well. Most of the low temperatures have never been equaled. The storm was actually the worst part of a bad winter. It came in late January and the temperatures dropped to between thirty and forty degrees below zero. The wind was estimated to be in excess of fifty miles per hour.

The storm drove many range cattle in search of shelter into ravines where they perished. But in Hull, Nebraska a large number of bulls used the Hull country store as a windbreak. They gathered there half crazed by fear and thirst. In such storms cattle often do not die of the cold but rather of dehydration (they will not eat snow to satisfy their thirst) and suffocation (due to nasal passages blocked by snow and frost). Unfortunately, these cattle positioned themselves between the Hull house and the water well, thus denying the family access to water. Three days into the storm, fuel began to run low. Albert and Etta were facing a choice of being frozen to death or dying of thirst. As is so often true in life, the crisis passed as suddenly as it arose. On the fourth day, the storm abated and the bulls that had survived wandered away. Upon checking the barn, Albert found his only horse dead in his stall, frozen in a standing position. The powder-like snow had forced its way through every crevice and crack and the interior of the barn was filled to a depth of nearly six feet. Tied by a halter in the stall and unable to move about, the animal had suffocated.

Albert and Etta Hull remained in Nebraska three more years and it was here that their only child, Afton Miller Hull, was born on September 17, 1890. The following year, the family returned to Taintor, Iowa where Albert once again served as a postmaster and owner/manager of a General Store in Taintor. In addition, he steadily acquired land over the years using his own money as collateral for loans. He was never a farmer in the true sense of the word. He was a naturalist: he loved his garden, flowers, and trees. But first and foremost, he was a merchant and a manager of resources. His son, Afton, and later his grandchildren worked the land and tended the livestock. Albert B. Hull used his pencil and his head and was the epitome of a shrewd businessman.

Albert B. Hull was my grandfather and was almost fifty-eight years old when I was born (almost the same age difference as between my grandson, Bill Lisle, and myself). His relationship with his grandchildren was of an idyllic nature so common during the earlier part of this century. It was not an occasional relationship, but a daily, almost hourly association that seems to a child to go on forever.

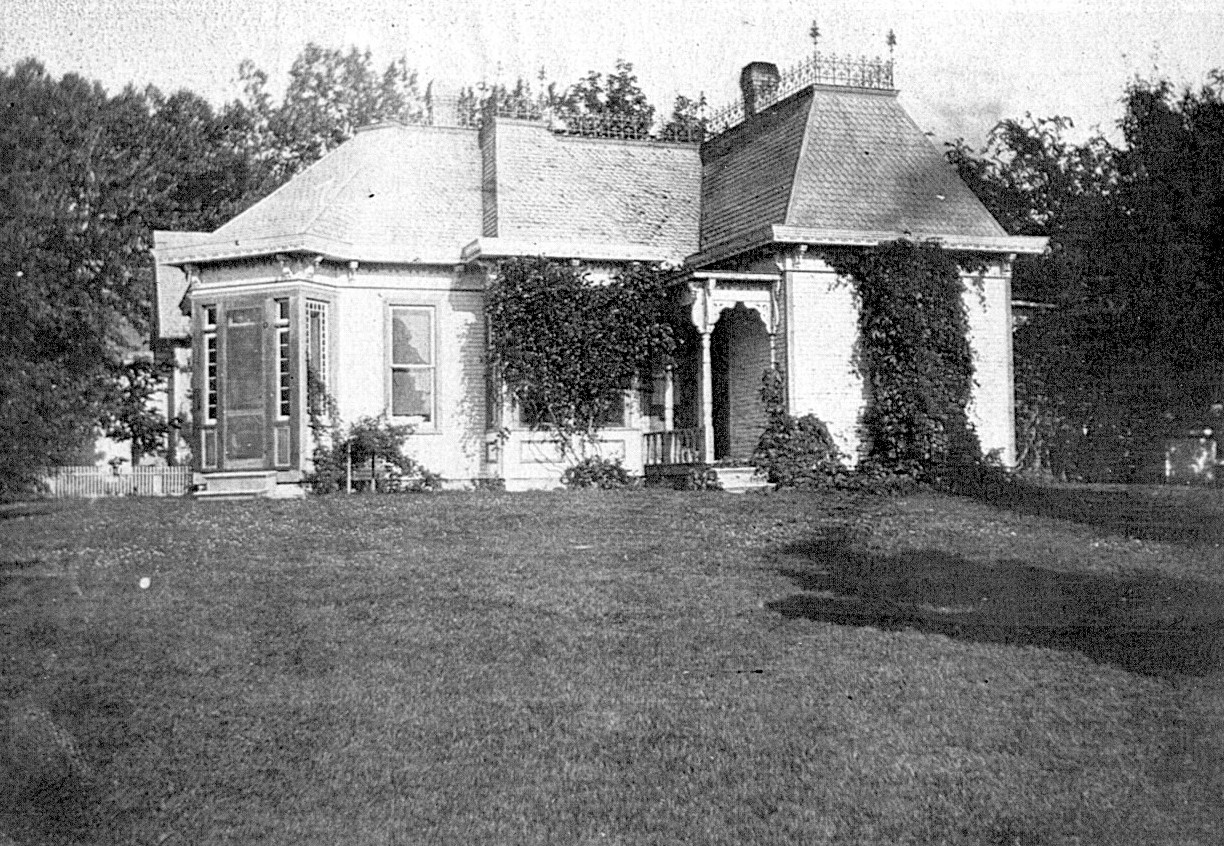

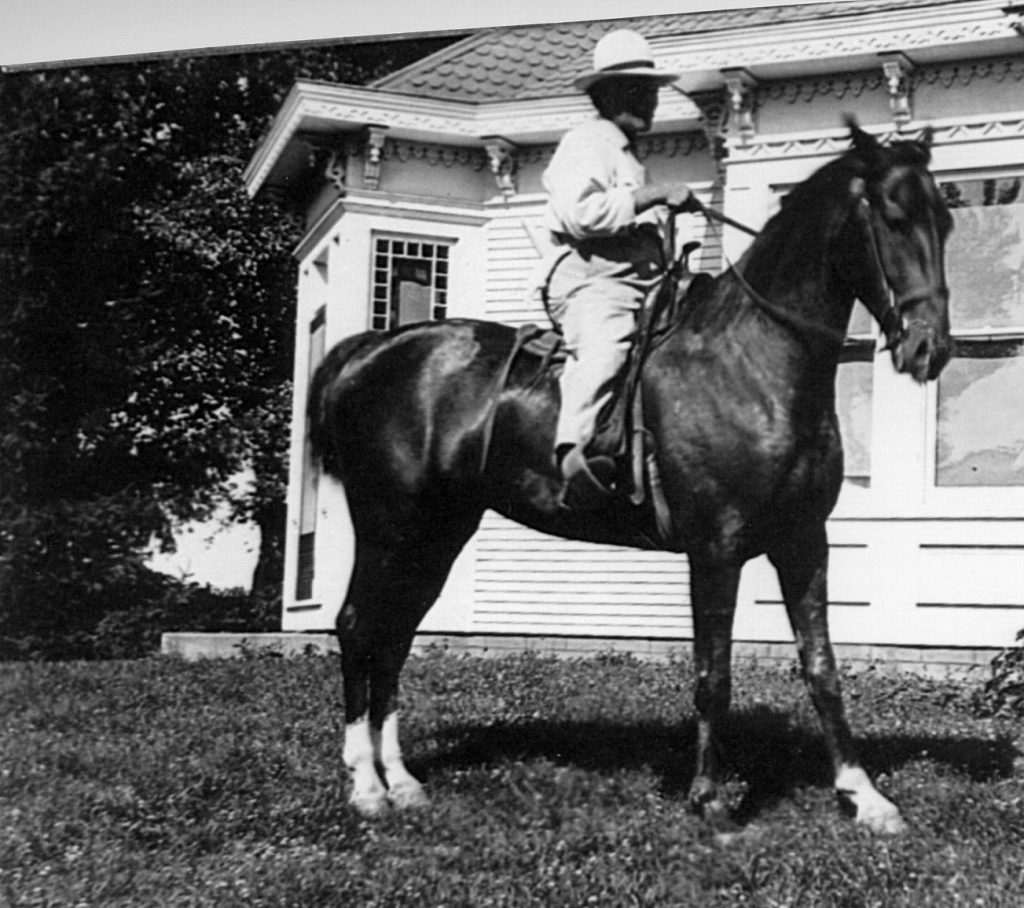

The house where my father (Afton Miller Hull) was raised and where grandfather lived for forty-six years was about two city blocks from our home, and an equal distance from the feedlots, and barns. He tended a large garden at each location, kept a small flock of chickens and one milk cow that was “stanchioned” daily with our herd. The cow’s name was “Buttercup” and she was a prized possession to the point of being treated as one of the family. I can still see Grandfather, morning and evening, hunched down on his three legged stool, head in her flank, straw hat shoved back on his balding head, surrounded by an aroma of cigar smoke, stroking away with the regularity of a metronome.

He always took time to make a whistle from a weeping willow tree branch, to repair a toy, or to find a perfect fork in a branch for a sling shot. He always took time to talk to us too (not idly, as one might talk to a child, but in a serious vein). When he talked, his mood was jocular and his eyes danced as if he would share a secret with you if you listened. You were never disappointed. He seemed to be surrounded by an aura of tranquility and yet one was immediately aware of an inner strength, a purpose, a quiet determination. I do not recall him ever raising his voice; but more than that, I remember that when he did speak people listened.

An incident that illustrates the character of the man took place in 1933. It was three and one-half years after the stock market crash of 1929. The country was in the depths of the Great Depression. Banks were closing. Mortgage foreclosures were common. Grain and livestock were nearly worthless. Rumors of all kinds were rampant. One of the rumors was the Mahaska County Bank in Oskaloosa (the County seat), was nearly bankrupt. My father, Afton Hull, believed the rumors and to protect his interests he withdrew his money and purchased a small farm (80 acres) not far from home. Grandfather did not appear to be alarmed. Dad did everything possible to persuade Grandfather to withdraw his funds before it was too late. Finally, Grandfather agreed to go to the bank and talk to the president. I accompanied them and the argument continued all the way to the bank. On arrival, Dad and I remained in the car while Grandfather went inside. An hour or more passed before he reappeared. After he settled into the car, he quietly informed us that he had been assured there was no basis for the rumors and no threat to the security of his money. Dad lost his temper and berated Grandfather mercilessly. Finally, after a period of silence, Grandfather said quietly, “I have known Harry Howard all my life. We went to school together. I trust him. If I did withdraw my money, it could very well cause a “run” on the bank should word of my withdrawal get out to other depositors. That would be a catastrophe. The subject is closed, take me home.”

For a twelve year old boy, that was the longest twenty miles I ever rode in a car. Not a word was spoken. Stony silence prevailed until we stopped at Grandpa’s house. He put his hand on my knee and spoke quietly to both of us: “Boys, this won’t seem nearly so important when you’re an old man.” He opened the car door, got out, and slowly walked away.

A few days later, I was struggling with the lawnmower at Grandpa’s house. He was lying down, resting under his favorite tree, an old straw hat covering his face to shut out the glare of the sun. With one knee raised akimbo over the other, hands clasped across his chest, he was the picture of tranquility. Suddenly, Dad appeared with the news. The bank was in receivership, the money was gone. Dad was frustrated and angry, but the man who had lost his life savings (slightly more than eighty thousand dollars) was to all appearances unmoved. He slowly moved the straw hat from his face to his chest and silenced Father with, “We still have the land. I started with nothing. It’s all part of living. You are still better off than anyone I know. We won’t talk about this again.” With that he placed the hat back on his face. The subject was closed and to my knowledge remained so.

I have often thought about Grandfather’s last few years. They seemed to be a combination of drought, dust storms, depression, and failing health. Cattle bought at $7.50 per hundred weight were sold at $3.00 per hundred weight. It was 1934 and for the first and only time in Iowa’s history there was total drought. The herd was decimated with Bang’s disease (a form of T.B.) and those infected had to be destroyed. Skinning bloated cattle, salting down hides, and assisting the scavenger trucks that came to haul them to the rendering works seemed almost a daily occurrence.

Our horses became afflicted with encephalitis (also called sleeping sickness), an inflammation of the brain later found to be transmitted by a particular type of mosquito. We lost six Belgian draft horses and Grandfather’s favorite saddle horse. The following year, two hundred hogs ready for market died of cholera. At the same time, we were forced to kill most of our little pigs because the government said that alleviating the existing surplus would raise prices. (It’s pretty hard to sell a pig for a higher price when you’ve just hit him in the head with a hammer).

On a Saturday afternoon in 1937, Dad and I were breaking a young colt to harness. The two year old was hitched to a heavy wagon with a larger, older horse. It’s front legs were hobbled (loosely tied together to allow walking but prevent it from bolting). I rode in the wagon with Dad and handled the jerk rope while he drove the horses. We drove down the alley behind Grandfather’s house to show him the team. When he came to the door, he also had something to show us. It was a beautiful rose he had inbred. Standing there in the doorway, smiling with the ever present cigar in one hand and the rose in the other, it was the last time I was to see him alive. That evening, while in New Sharon shopping, we received a phone call to come home immediately. A neighbor walking by their home had heard Grandmother call out. Grandfather had died quietly in his sleep.

We were there in a few minutes. After consoling Grandmother, Dad asked me if I wanted to go into the bedroom and see Grandfather, not knowing that in the interim the undertaker and his assistant had arrived and (as was the custom in those days) already begun their work. It was a scene and an experience that I accepted with equanimity but never forgot.

It was not until the following morning when I had finished milking and was letting the cows out to pasture that I confronted the hired man for the first time since Grandfather’s death. We met in the center of a dusty lot and the totality of recent events enveloped us with a flood of emotion. We clung together for mutual support and wept unashamedly. Finally, we broke apart and stumbled in opposite directions. Neither of us had said a word throughout.

So much has happened since that day so long ago, but I still choke up when I remember a seventeen year old boy sitting alone for hours, racked with grief. I honestly believe I know what it is like to die of a broken heart.